Jet or The Effect of Elephant Tranquilliser on Short-Term Memory

(extracted from (the entirely fictitious) ‘By Accident to the Orient, and Back Again – A Wasted Life’ by Martin Gordon

It’s now June 1974 and I am replaced in Sparks’ affections by Jook’s more suggestible bassist. Jook, an apparently violent collection of skinheads, are managed by the same person who manages the band Sparks, of whom I have recently been a member. This is John Hewlett, formerly bass player with John’s Children. Their skinhead nature bears as much relation to reality as do the circumlocutions of their (or, to be precise, our) manager Hewlett. But this does not become apparent to me for some considerable time. So I am offed from Sparks, and Jook effectively become defunct, as their guitarist Trevor White is also offered an appropriately small commission at the same time as their anonymous bassist. Being no longer gainfully employed, and in a similar position to me financially, and also morally, Jook’s drummer Townson calls me up. I am wary of his apparently skinhead nature, but it soon turns out to be only a showbiz jape. It’s a gimmick, darling, a gimmick! Sparks manager John Hewlett has suggested that Jook could keep going with me in place of the recently-departed bass player, but Chris and I feel that whatever we might pursue, it will be much improved by an absence of Hewlett. Chris mentions that he has a friend who is a singer, called Andy Ellison, who perhaps would be interested in coming along.

‘Two shadowy figures from the golden age of Middle Earth’ is how journalist Chris Welch rather bafflingly referred to Andy Ellison and Chris Townson, obviously getting his Tolkien mixed up with his Tennents Super Lager. What he meant (possibly) is that both had been in the infamous John’s Children in the late 60’s, along with Marc Bolan on guitar and the previously-mentioned John Hewlett on bass. Managed by Simon Napier-Bell, subsequently to mastermind the career of Wham, they were banned from the UK airwaves thanks to their risque lyrics and then thrown off a German tour with the Who for upstaging Townshend and co. John’s Children’s brief career was effectively ended. Being old school pals, Chris and Andy kept in touch.

At this time Peter Banks also calls. Perhaps feeling solidarity with my position, he is the former guitarist with Yes and was unceremoniously slung out once they became successful. I have a brief get-together with his new band Flash, but frankly the compound time signatures and asymmetric metres make me feel dizzy. I am detained only as long as a single rehearsal in Kings Cross, London, and then return to the rumpty-tumpty (as it will turn out to be) fold.

Chris suggests to Andy that we should all meet up. Ellison puts on his green anorak and we do just that. We book time in a rehearsal complex owned by the Equals, Eddie Grant’s band. Bashing away as a trio, even though it’s only bass, drums and vocals, we feel we have something worth pursuing. Also worth pursuing are the thieves who break in on the first night and steal Chris’s much-prized silver drum kit. The Equals, who are clearly above suspicion, declare their outrage. Borrowing another kit, we put an ad in Melody Maker. A multitude of weirdos emerge, along with the girlfriends to whom they perform whilst auditioning, and they include Ian Macleod. Decidedly un-weird, Ian gets the gig, and he and his guitar are duly enrolled. we decide to call the band Jet. But there’s some eccentric spark still missing…

At the time, Bryan Ferry’s version of the Dobie Gray tune ‘The In Crowd’ is being played day and night on the radio, in two versions. One is a radio-friendly three minutes while the other features a full length guitar freakout. The acid weirdness of the outro prompts us to track down the responsible party, and this is David O’List. Davey has been in the Nice, he’s been in Jethro Tull, he’s depped for Syd Barrett in the Pink Floyd and he’s just been replaced in Roxy Music by Phil Manzanera. Frankly, he’s been around a bit. His phone number is left with my telephone answering service by his management company. In retrospect, this should have flagged up a warning sign. We arrange to meet.

At the time, Bryan Ferry’s version of the Dobie Gray tune ‘The In Crowd’ is being played day and night on the radio, in two versions. One is a radio-friendly three minutes while the other features a full length guitar freakout. The acid weirdness of the outro prompts us to track down the responsible party, and this is David O’List. Davey has been in the Nice, he’s been in Jethro Tull, he’s depped for Syd Barrett in the Pink Floyd and he’s just been replaced in Roxy Music by Phil Manzanera. Frankly, he’s been around a bit. His phone number is left with my telephone answering service by his management company. In retrospect, this should have flagged up a warning sign. We arrange to meet.

When Sparks and I go our separate ways, they also ditch Sir ‘Peter’ Oxendale, who was destined not to play the complicated (I use the term relatively) keyboard parts that their main keyboard player Reg Mole was unable to play. Peter uses the same telephone answering service as I do and among his annoying habits is that of picking up other people’s messages. (In those pre-technological times before answering machines, there were people who would answer the phone for you, and give you, or indeed anyone at all, a list of names and numbers of those who had called you during the day, for you to call back.) Oxendale intercepts my calls to and from O’List and takes strategic action. When O’List arrives for our subsequent meeting, Peter is accompanying him. It seems, like it or not, that Jet has a keyboard player.

Oxendale’s rather different version of this evening in the pub is published in Melody Maker. I discover that he is “forming a band with Davey O’List and Andy Ellison who I met at a club I own in Paris”.

In late June, Jet enter TW Studios in West London. The engineer is Alan Winstanley, who later produces Madness. I pay the bill and produce the outcome, three songs which we believe demonstrate our burgeoning talent. ‘My River’ is an O’List tune, ‘Start Here’ is one of mine and ‘Desdemona’ is a Marc Bolan song from John’s Children days, in fact their biggest hit. O’List’s guitar playing is not affected by his falling over flat on his back during the take. In retrospect, it is the first indication we have of his idiosyncratic world view. Simon Napier-Bell turns up to see what’s happening but decides that the future does not lie with prone guitarists, and of course he is later proved correct, with Japan, Wham and George Michael, none of whom were remotely prone, unless it was artistically relevant or helped their careers.

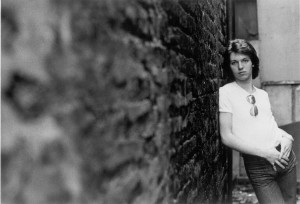

| Sing! | Bass! | Drum! | Cheese! | What the F! |

|

|

|

|

|

| Andy Ellison | Martin Gordon | Chris Townson | Peter Oxendale | Davey O’List |

Jet send copies of the resulting tape around the music business. One finds its way to Jamie Turner, and he passes it on to Mike Leander, manager of Gary Glitter, producer of Cliff Richard and arranger of Beatles string parts. Mike signs the band for management and enrolls Jamie as our personal factotum. We rehearse at the Furniture Cave, more out of habit than conscious decision – this is where Sparks polished ‘Kimono My House’ into it’s final form. It is as depressing as usual, leading us into frequent assaults upon our equipment, usually after a lunchtime Special Brew or four in the local pub, the infamous Roebuck.

A few weeks later, Leander procures an audition for CBS (as they then are) in their Whitfield Street studios in London. An employee has thoughtfully provided a tape of massed applause to be played at the end of every song. There are eight people in the enormous studio, including the band. Later Andy says ‘I didn’t really know what to do at the audition – we’d end a number and from three people would come this kind of Nuremberg Rally effect. I just treated it as a gig and jumped around a lot’. His jumping around has the desired effect and the band are signed, via Leander, to a recording deal. When the ceremony takes place, there is a contract face down on the table, with the last page turned over ready for signing. I attempt to take a look at it, but am told it is none of my business. The band sign. (I finally see the contract for the first time in 2004).

We record more demos. Nicky Graham, later to reach notoriety with boy-band Bros, produces them. The result is unimpressive. A third round of demos is embarked upon, this time produced by me. The results are more impressive (but of course) and also considerably more expensive. Which was not surprising, as I had pressed all three recording and editing suites at Trident Studios into simultaneous service. ‘Four thousand pounds?!?’ shrieks Leander, as he hurls the cassette with three songs on it across the table at Jet’s weekly meeting with management. ‘For THIS?!?!’ He takes matters into his own hands and sends for Roy Thomas Baker to produce the band.

Baker has productions of Queen, the Cars and Foreigner under his belt. Jamie Turner contacts him and plays him the tapes. Rimour has it that visionaries at CBS suggest to him that the band should be made to sound like Sparks but, to his credit, other rumours indicate he refuses to go along with this. When we finally meet, I’m surprised to find that I recognise him – he lives in the flat above me in a mansion block in Putney, South London. From time to time, he drops me at the tube station in his Jaguar, while he drives off to the studio where we’re both working. I am usually late in arriving, due to the sluggish London tube, but Roy zips through the traffic without a care in the world.

The sessions start at Sarm Studios in London’s East End in November 1974, and continue till January ’75. Baker initially tries to record all the musicians simultaneously, but it doesn’t work so individuals drop out one by one. Eventually all the tracks begin life with just bass and drums. On one occasion, engineer Gary Lyons comments ironically through the headphones to Chris and I, as we struggle manfully with ‘Tittle-Tattle’. ‘That’s it, faster! Faster!!’ he critiques as we speed inexorably up. There are no click tracks in these Neanderthal days of technology. Chris throws down his sticks and runs manically into the control room. Gary has thought better of his infelicity and, perhaps fortunately for the Rolling Stones, is no longer present.

Not surprisingly, internal relationships degenerate. We spend entire days tuning up. ‘Boing, scrape, boing-ng-ng’ goes the guitar, for hour after hour. Band members turn up at midday, wait around for five hours of tuning and then disappear without anything being recorded. One reason why the guitar only stays in tune for a pico-second is that O’List has removed three of the five tensioning springs from the back of his Stratocaster. When this is pointed out as a possible causal factor, he says that it makes it easier to bend the strings. This cannot be (and indeed is not) denied.

Roy Baker saves the day with his lightning wit and repartee, and also his extensive collection of Scandinavian pornography featuring donkeys. Gary Lyons demonstrates his prowess as fork soloist, and his expertise proves to be a key feature of ‘Quandary’. Roy finds time to demonstrate his new guitar effects unit to O’List – you play a guitar straight into it and what comes out is completely unrecognisable. O’List is intrigued – is this the direction in which guitar playing is going to develop? His mind boggles visibly. He plays in some mindbending widdly-widdly , and out comes a incompetent rendition of a twelve bar blues. This is cutting edge, outside-the-box technology and no mistake.

In fact the device is less outside-the-box than out-of-yer head technology. A pissed Chris Townson, lying down out of sight in the studio and flailing at one of O’List’s spare guitars, with a bottle of Johnnie Walker at his side. When he hears something in his headphones, he flails madly at his guitar in response. We all feign amazement at the state of the technological art.

O’List’s girlfriend turns up and falls drunkenly asleep with her paramour under the grand piano. When the duo begin to emit stentorian snores, we mike them up, adding expensive (stereo!) delays and reverb and we record the whole thing to multitrack, which occupies us for a whole evening. When the duo awake, they are not amused by our soundscape. Andy Ellison turns up one night dressed as a policeman, closely followed by the owner of the uniform, who is in fact a real policeman. The office of the law is most impressed by the goings-on, and lends us his police badge to help in the preparation of illegal substances.

O’List’s girlfriend turns up and falls drunkenly asleep with her paramour under the grand piano. When the duo begin to emit stentorian snores, we mike them up, adding expensive (stereo!) delays and reverb and we record the whole thing to multitrack, which occupies us for a whole evening. When the duo awake, they are not amused by our soundscape. Andy Ellison turns up one night dressed as a policeman, closely followed by the owner of the uniform, who is in fact a real policeman. The office of the law is most impressed by the goings-on, and lends us his police badge to help in the preparation of illegal substances.

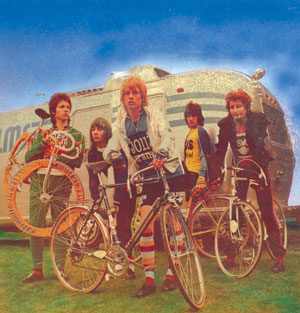

Despite these and other diversions, the album is eventually finished. An expensive photo session is organised at Mick Jagger’s medieval home Stargroves. Parked round the back is a shiny Winnebago caravan and, in front of it, unaccountably sitting on racing bikes and dressed in the latest tadger-revealing racing-bike chic, are the five members of Jet. They are suffering still from the previous night’s drinking session and looking excruciatingly cold as the icy February gales whistle around their nether regions. Not helping is the lack of sleep – following the previous night’s piss-up, I fall into the River Thames whilst the band is pouring me back into my houseboat; the keys to the group car fall into the luxuriant Thames mud along with me, ensuring that a relaxing night in the arms of Orpheus is not had by all.

After the expensive racing bikes and tat are returned, the expensive photographer takes the expensive pix to an expensive artwork company who prepare an expensive record cover. The management present CBS with the result, based on a Chris Townson design, and the band announced that the record is to be called ‘Has Anyone Seen Charlotte?’, after a song of the almost same name. ‘Dreadful!’, respond the record company to both sleeve and title. In a fit of spite, they decide it will be called ‘Jet’. It is given a sleeve by Roslav Szaybo and the CBS in-house art department which is a straight lift from Marvel Comics’ Mr Miracle, for which CBS are later, quite rightly, sued.