[modula id=”6165″]

Under the umbrella of Island Records, Richard Digby Smith has engineered and produced recordings by some of the rock world’s most legendary and influential performers. Taking a quick gander at the carousel up above will show that the list includes Free/Bad Company, MacDonald and Giles, Mott the Hoople, Spooky Tooth’s Mike Harrison, Patto/Boxer, John Martyn, Robert Palmer, Jethro Tull and Led Zeppelin. For the latter, he was part of the engineering team for Led Zeppelin III and IV, including that tune: Stairway to Heaven. Island Records, it must be said, captured the rock zeitgeist.

Under the umbrella of Island Records, Richard Digby Smith has engineered and produced recordings by some of the rock world’s most legendary and influential performers. Taking a quick gander at the carousel up above will show that the list includes Free/Bad Company, MacDonald and Giles, Mott the Hoople, Spooky Tooth’s Mike Harrison, Patto/Boxer, John Martyn, Robert Palmer, Jethro Tull and Led Zeppelin. For the latter, he was part of the engineering team for Led Zeppelin III and IV, including that tune: Stairway to Heaven. Island Records, it must be said, captured the rock zeitgeist.

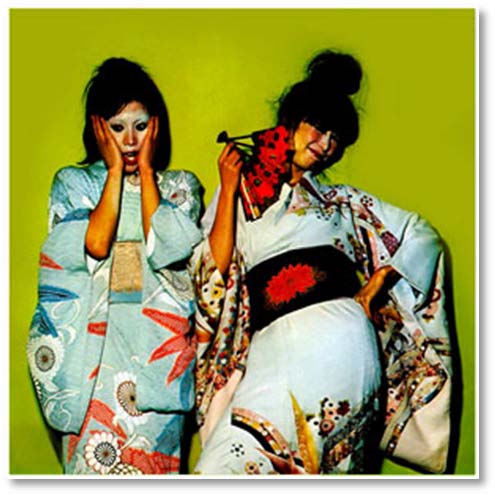

And to add to the list, there’s also the album Kimono My House by Sparks. As bassist for that band, Digby and I first met in 1973 (he was then known as Diga) in Island’s Basing Street studios. I was a neophyte bassist, he was running the board, liaising between upstairs and downstairs and making sure that everything sounded as divine as it possibly could, interventions and outrageous requests notwithstanding. Subsequently, people seemed to like it.

After a gap of a mere quarter of a century, I discovered that Digby is now running his own recording and mastering operation in the UK. So I thought – who better to tweak my bass, and indeed all the rest of the instruments, in my latest deluded effort to save the puffins than Richard Digby Smith? And so it transpired.

Following Digby’s masterful tweakery of the upcoming Thanks For All the Fish album, I posed a few questions to him, to which he was kind enough to respond. He will be going into (much) more depth in his upcoming biography, which I for one will be adding to my wish-list for Xmas 2018.

In December 2017, we spoke about Richard Digby Smith’s illustrious history.

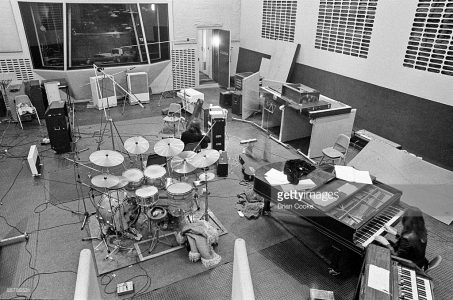

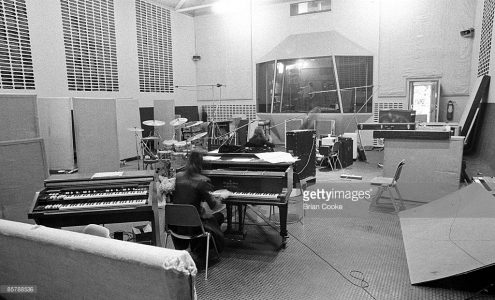

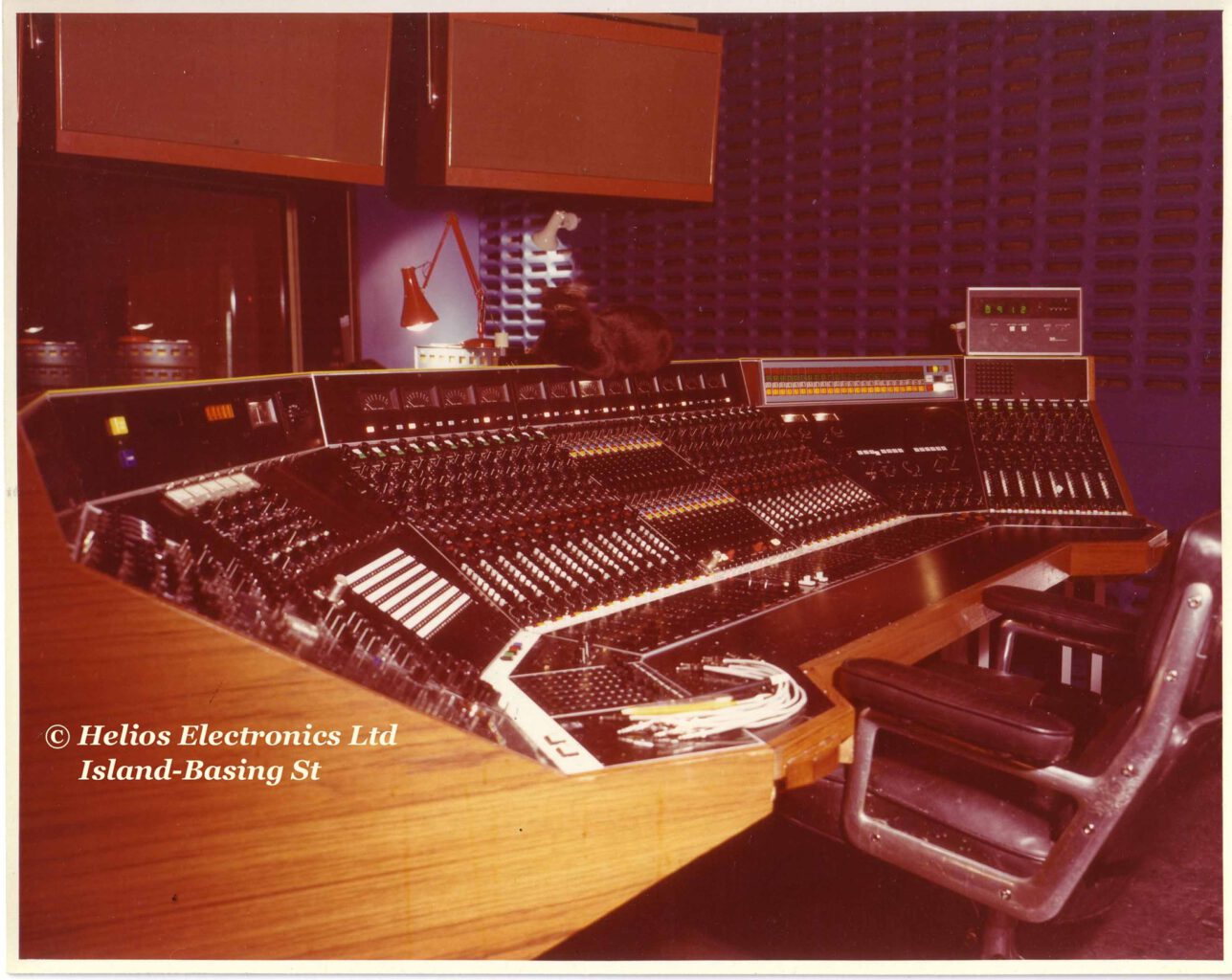

Q How did you wind up being the house engineer at the legendary Basing Street, home to Island Records?

RDS In late 1969, I had visited London with a list of 38 recording studios, courtesy of researching a London telephone directory on my lunch break. After three days of “pavement-pounding” I arrived at Maximum Sound on the Old Kent Road, number 38 on my list. He gave me a contact number and a name and so, on a cold, wet October evening I walked into Island Records’ Basing Street facility and asked for a job. I moved to London from my home town of Birmingham, aged nineteen, in January 1970, and began working in the music industry as a tea-boy, van-driver, gofer and trainee tape operator for Island.

Q You’ve worked with some of my favourite artists and on some of my favourite albums. Let’s begin with ‘Kimono My House’. I remember you in the studio as being a very friendly chap, which was important for those of us who hadn’t been in studios before (namely me). I also remember getting the bass sounding right took a good while, due to my insistence on using an small (2 x 8″, for those who care about these things) H&H combo, but we got it sounding great, as the b-side to This Town, the tune Barbecutie, demonstrates. Do you have any recollections of those sessions, both at Basing Street and also at the Who’s studio Ramport, in Battersea?

RDS By the time I got to working with you on the first Sparks album, I had already developed a close relationship with Muff Winwood, working with The Sutherland Brothers and Patto. Basing Street must have not been available so we went to Ramport. It was a refreshing change of scenery for me. From my perspective, you were no more demanding than anyone else! H+H combo or otherwise! As a full-time staff engineer for Island, working on three or four albums at any one time, Sparks were, to be honest, just another band in a long list of continuous sessions.

Having said that, it was apparent early on that here was something special and unique sounding. Muff was always to be trusted when it came to spotting talent, and I remember the sessions as being quite joyful and productive. And very high-fashion chic!

Q And then one day, when I came into the studio, suddenly This Town had gunshots on it, which I seem to recall was your idea…?

RDS I thought that This Town… had something of the “High Noon” about it, so gun-shots had to be in there somewhere!

Q I don’t know why Muff Winwood decided to mix KMH with Bill Price rather than with you. Did you mind not mixing it?

RDS It was/is not uncommon to have another engineer mix tracks that you had recorded. Always useful to employ a fresh pair of ears, so it was neither surprising or disappointing.

Q Was there much leeway in your working relationship with Muff? I recall that he was less of a technician than an ‘ideas’ man.

RDS Muff was the easiest, most relaxed and knowledgeable producer any engineer could wish to work with. No airs or graces, no “show-biz” ego, just a totally down to earth, methodical approach. And always good humoured. As a musician himself and having recorded hits with the Spencer Davis Group, Muff knew the studio process well. I learned much from the great man.

Q I recall Paul Kossoff looked into studio 1 in Basing Street while I was replacing the bass on Amateur Hour. I don’t know if you remember that – I had to replace an amped version with a DI rerecording, about which I was most miffed. I guess Paul dropped by to see you, as you’d worked with Free and then on Kossoff’s solo album Back Street Crawler and the Kirke Kossoff Testu Rabbit album.

RDS Where to start with Paul Kossoff and Free? So many sessions, so many albums, so many tales. Here’s just one:

Kossy’s Marshall amp was set-up in studio two at Basing Street, on standby. We were in the middle of a guitar overdub and he had wondered off for a short break.

Some would-be aspiring guitarist was walking past the studio and walked in, uninvited, and grabbed Paul’s treasured Les Paul. I pressed the studio talk-back and yelled “Don’t touch that guitar” but it was too late. This impostor had the guitar in his hands and switched off the stand-by. All hell broke loose as the feedback and distortion became unbearable.

I marched into the studio to reprimand the intruder and heard him mumble something along the lines of “How can anyone play this pile of shit…“ He begrudgingly replaced the guitar back on its stand and I escorted him out of the room. Kossy returned, picked up the guitar, switched off the standby, and returned to his beautifully sustained legato and melodic sweeping phrases. The Les Paul was back in the hands of its rightful owner.

Paul was such a kind, caring and witty man. No one before, or since, can make the electric guitar sound so like an uninterrupted extension of the human soul as he. Such a sad loss for his family. So young. I think about him often.

Q You were the house engineer at Basing Street, I guess. Did you work at St. Peter’s Square as well?

RDS As one of Island’s staff engineers, you were often required to head across town to St. Peter’s Square and engineer there. Did a couple of albums with John Martyn at the Fallout Shelter as it was called. Spent a remarkable amount of time in the nearby Cross Keys pub, fine tuning my alcohol fitness regime.

Q You’ve cornered the market in my favourite singers, as I mentioned. And here they come. Mike Patto! Was it fun working with Boxer? Did you do any Patto (the band) albums?

RDS Recorded Boxer out at The Manor in Oxfordshire. Croquet on the lawn, dips in the pool and a banquet every night. Mike Patto’s one of my all-time favs as well. Great sense of the absurd, as was the case with guitarist Olly. Their manager, Nigel Thomas, was very kind to me. Lost my flat back in London due to a terrible flood. He put me and my girlfriend up at the Portobello hotel for four weeks after the Boxer album was complete whilst we got our lives sorted.

Q And then there’s Mike Harrison, one of the all-time great British voices. I know him slightly these days, as I found my guitarist Ralf Leeman playing in Mike’s band, and Mike and I have, over the years, had drinks together from time to time. How was he to work with? Any special demands?

RDS Mike Harrison would record endless vocal takes. His pursuit of excellence was unmatched. I most definitely fine-tuned my skills regarding vocal pitch and phrasing. Not to mention developing the high levels of tenacious patience required in achieving the artists’ objectives. Always great fun to be with, Mike and his band the Junkyard Angels have almost an entire chapter devoted to them in my forthcoming book. Drug bust et al.

Q There’s McDonald and Giles, of course, a great album, and some years later ‘Turnham Green’ was the source of Radio Star’s ‘Dirty Pictures’ riff, I have to confess. Having recorded it in St Peter’s Square, we later remixed it downstairs in Basing Street. Anything to relate?

RDS Worked with Island staff engineer (and fellow Brummie) Brian Humphries on the McDonald and Giles album, in studio two at Basing Street. My first professional album. Again, an extremely demanding project in terms of patient, almost relentless attention to detail. A baptism of fire for the studio life that lay ahead for me.

Q And there’s Free. I think Free At Last is one of their finest, despite the probably trying circumstances under which it was recorded. And what a great player Andy Fraser was.

RDS I was a massive fan of Free, back home in Brum, long before I moved to London. From early sessions assisting with Andy Johns on Highway, I was to be involved on about three albums with these guys and most recently mixed a Bad Company live album set. Andy Fraser was the quiet one, but most involved in the production, which always featured his unique style of bass playing.

Q I believe some of the guitar parts were played by Rogers, were they not?

RDS Paul R. did play some of the guitar on Free At Last and also with his own band, Peace, which I recorded at Basing Street. I recorded with Kossy out in New York and Los Angeles with his band Back Street Crawler. I was with him in the studio on his last ever session, just before he died.

Q Robert Palmer was always a favourite of mine as well, and I had the good fortune to mime with him on a performance of Addicted to Love for some dodgy TV show. My nose was never the same again. Yours?

RDS Recorded with Robert Palmer at Clover studios in L.A., with the guys from Little Feat and Muscle Shoals producer Steve Smith. We made a devoted attempt, during the recording of Robert’s Some People Can Do What They Like album, to prop-up the economy of South America.

Q And that’s not to mention Jethro Tull, Bad Company, Mott the Hoople and, possibly the most famous of them all, Led Zeppelin. Is it correct that you engineered the guitar solo on Stairway to Heaven? That was at St. Peter’s Square, I believe…?

RDS Assisted, again with Andy Johns, on Zep III and IV. Mixing in studio two at Basing Street on the former, and mixing and recording the latter in studio one, including the recording of Stairway to Heaven. I compiled three takes of the guitar solo as Andy Johns looked on! Fellow Island engineer Phil Brown recalls in his book ‘Are We Still Rolling’ that Jimmy Page re-recorded the solo, with Phil engineering, so not sure which version made it onto the record. It must also be noted that the version of Stairway that was recorded with me and Andy Johns at Basing Street has been referred to as the ‘Sunset Sound Mix’ so not sure what that is all about. But in any event, I go into more detail in my book!

Q Do you have any favourites out of all the illustrious work that you’ve done?

RDS Well, Kimono would be one! Also, Prefab Sprout’s Protest Songs album, Hamish Stuart’s (ex-Average White Band) Sooner or Later album and most recently, an album with local Devon based singer/songwriter Anthony Lane called Look What We’ve Become.

Q How have you managed the leap into the digital world? Was it painless?

RDS It hasn’t required a “leap” into the world of digital. I can remember the first cassette recorders, the first drum machines and synthesisers. The introduction of 24 track analogue, 48 track digital. The first samplers, midi sequencers and DAWs. It’s been a gradual affair, this introduction of new technologies. And at every step of the way, each invention has been derided by some as being “THE END” of music and musicians. Ain’t happened yet! Yes, admittedly things have changed, but they always were changing. Nothing ever stays the same. Just keep up!

- Richard Digby Smith’s studio: www.tq1music.com

- and he has written a great and fact-filled account of those legendary days at Island