An interview conducted on 8/11/2007 for DOLL magazine, Japan.

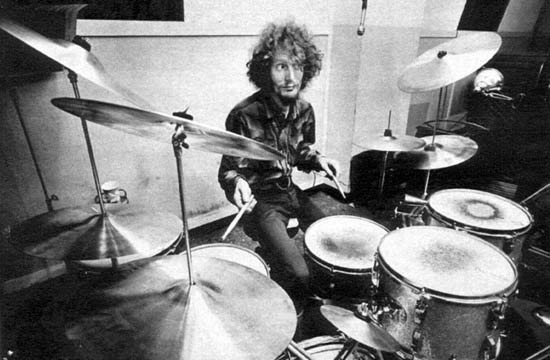

Martin Gordon reads out the questions on behalf of Kiyohiro Shiroya, Chris Townson provides his overview of his life and times and wanders down the odd interesting blind alley.

How did you begin playing drums?

When I was at boarding school we used to have what were called ‘parent weekends’ and of course I had no parents who would come and visit me, so I used to get invited out to friends of mine. I went out to a friend of mine who lived in Sevenoaks and his father was a jazz drummer. He had a rehearsal room set up, with the kit facing these big speakers and he’d play along to big band stuff. I had a go at that, just messing around. I had no interest in playing drums but there was a feeling, I remember very strongly that I could feel that there was a kind of … it wasn’t an upfront ‘Yes, I can do this’ but while I was doing it I thought ‘Yeah….’. And then later – 1964, ‘65 – if you went to art college, which I did, you went there to join a rock’n’roll band really, degrees and stuff were what you did after rehearsal.

When I was at boarding school we used to have what were called ‘parent weekends’ and of course I had no parents who would come and visit me, so I used to get invited out to friends of mine. I went out to a friend of mine who lived in Sevenoaks and his father was a jazz drummer. He had a rehearsal room set up, with the kit facing these big speakers and he’d play along to big band stuff. I had a go at that, just messing around. I had no interest in playing drums but there was a feeling, I remember very strongly that I could feel that there was a kind of … it wasn’t an upfront ‘Yes, I can do this’ but while I was doing it I thought ‘Yeah….’. And then later – 1964, ‘65 – if you went to art college, which I did, you went there to join a rock’n’roll band really, degrees and stuff were what you did after rehearsal.

This is the Pete Townsend model?

Yes. I actually learnt the famous three chords on guitar and considered myself a guitarist before drumming. So I met somebody and got into conversations about playing. ‘I hear you’re getting a band together’ – his response to me was ‘Yes, but we actually are having a problem with a drummer, we’ve got a guitarist’.

Was this someone we know?

This was Chris Dawsett. I’d gone to see his father one evening round at his house to discuss a career in art, and all I could hear was Chris plonking away in the other room, so I got a bit sidetracked. At the first opportunity, I had a chat with Chris. He said they’d got another guitarist, they’d got the bass player and what they were looking was a drummer. His sister, who was about nine or something, was bashing the drums in the corner at the time.

So you said ‘I could do that!’

Precisely those words. ‘I can play drums!’ And I threw her from the room. Do you remember those things called Gigsters? There was a snare about 2 1/2 inches wide and a hi-hat pinioned to the bottom. And that was it – I thought I can’t really go wrong here. I thought if I can keep time, they’d think ‘oh yes, he really CAN play drums’.

No bass drum?

No bass drum, I just stamped on the floor. Which I believe most of the blues musicians usually did. So we agreed that we would move forward. We were playing this turgid old blues stuff; it wasn’t really difficult to do it.

If you’re talking about drums and who I like, I don’t remember having a particular drummer that I was into apart from the Graham Bond Organisation – Ginger Baker. He was something else. I’d hear other drummers – to me they were quite adequate but slightly boring. Once I heard Ginger, I suddenly thought ‘hang on, there’s more’.

What was special about what he did? Was he playing the way he did in Cream?

Definitely – not so many toms, but he was playing very loud, Jack Bruce was very loud too, they were battling each other, and Baker had a very high cymbal, really high and he clattered away on the bell the whole time, really banging away and he played lots of rim shots. Lots of drummers were playing with this crisp hit on the snare head – he didn’t, he hit the side as a rim shot. There was just more dynamics to it. So he impressed me more than any drummer that I’d seen and I suppose he’d be the one person that I would name if someone asked me to pick one influence.

Definitely – not so many toms, but he was playing very loud, Jack Bruce was very loud too, they were battling each other, and Baker had a very high cymbal, really high and he clattered away on the bell the whole time, really banging away and he played lots of rim shots. Lots of drummers were playing with this crisp hit on the snare head – he didn’t, he hit the side as a rim shot. There was just more dynamics to it. So he impressed me more than any drummer that I’d seen and I suppose he’d be the one person that I would name if someone asked me to pick one influence.

Were there any other star drummers of the time?

No, it was the beginning of that transition period – of course it was Baker first, then Moon took it on. People always tied me in with Moon, but I don’t know why they did that – well, I suppose I do – the way I looked, we both ended up on Track Records, but funnily enough I didn’t really base my playing on him at all.

Style over content, in technical terms……?

Moon had his own persona, the drums fitted in with his persona rather than the other way round. And then of course you get the bottom line – there was only one Keith Moon, as clichéd as it sounds. I suppose I’ve nicked bits off him, here and there – ‘oh, that sounds good’. Sometimes if there’s a break, I don’t wait for it to come it, I’ll go thwack before the end, and off into the thing already playing. Own up time, I nicked that, and use it a lot, even to this day. It’s kind of second nature now to hit the snare before you go in, but that’s the only thing I can say that I nicked.

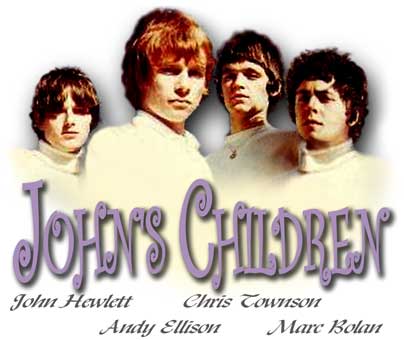

Then came John’s Children with Marc Bolan. After Marc left the band, you moved to guitar… How did that happen?

Then came John’s Children with Marc Bolan. After Marc left the band, you moved to guitar… How did that happen?

Well, at one point (manager) Simon Napier-Bell came up to me and said that Marc was leaving the band. We had some gigs set up in Germany, and we felt it was something that we couldn’t not do. For the television appearance, we were going to mime, so that didn’t matter but we had other gigs. We had one at the Star Club, where we took over from the Bee Gees. They were booked but had pulled out, we replaced them – which was pretty funny, because if someone asked me what is the worst band, the band that I hate the most, the band that I would smash televisions and windows to get away from, it’s the Bee Gees. That whole whining, nasal… oh, God! Help!

For the TV, we were actually billed above Hendrix, on the same show. Incredible… but we did the live gigs. And we did some gigs in the UK and it soon became apparent to me that I didn’t need to learn the whole set on guitar, so I didn’t bother. I learned four numbers – the fourth song in the set was Day Tripper – and then we smashed everything up. I’d start having fights with John and Andy after the bridge – ‘so long, to find out…”. That was the end of the gig. The audience thought they had about another hour to go but they soon got the picture. So that’s how I dealt with playing guitar.

The funny thing was that as we were going through Germany, one of the machine heads on the guitar broke, so each night the pitch was going down and down and we didn’t have time to fix it, so we just tuned down more and more. By the time it got to the fourth or fifth gig, it was just like the heavy metal guys of today, tuning down to low C.

Ahead of your time again, inadvertently.

Inadvertently. Anyway, during this last tour, I became so contemptuous of the whole thing by being part of it, by doing what I was doing, that finally I just threw the guitar into the audience, I just threw it away and walked off. And it came back! It was beautiful little white Telecaster. I threw it back again, and it didn’t come back. Simon said ‘What are you doing that for!?!’ I said ‘this is stupid, Simon!’

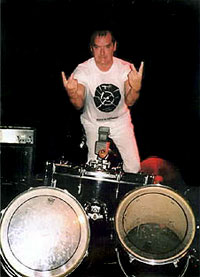

Who was drumming at that point?

Chris Colville. He was originally the roadie. Chris – if you took the actual sound away, he was the best drummer in the world. He was an archetypal Moon figure. He could do the most fantastic things, because he knew he was miming, of course, When it was live, he did the same, so we just turned everything up incredibly loud so that you couldn’t hear him. He did everything. Moon used to twiddle his drumsticks – Chris used to come on with sticks stuck in his hair, four sticks in each hand. He never played the top kit; it was all bottom kit – two bass drums.

Chris Colville. He was originally the roadie. Chris – if you took the actual sound away, he was the best drummer in the world. He was an archetypal Moon figure. He could do the most fantastic things, because he knew he was miming, of course, When it was live, he did the same, so we just turned everything up incredibly loud so that you couldn’t hear him. He did everything. Moon used to twiddle his drumsticks – Chris used to come on with sticks stuck in his hair, four sticks in each hand. He never played the top kit; it was all bottom kit – two bass drums.

What do you think of Simon Napier-Bell and his biograph?

I try to avoid his biograph at all times. The only biograph of Simon’s that I’ve read is ‘You Don’t Have To say You Love Me’ and I find it tacky, I wasn’t impressed with it, I didn’t want to read the other one. I bought it for Andy but I didn’t read it.

Was there a relationship with reality?

Yes, there was a relationship, some of the things around John’s Children, but it was Napier-Bell’s particular viewpoint. As for Simon, I have to say that I don’t have any problem with at all my own personal relationship with Simon. I found him good company, he found me good company. There were very few incidents of having to come to terms with his homosexuality – very few incidents, no big deals, just silliness after you got pissed. In the back of a Rolls Royce, he’d go ‘Come on, give us a kiss!’ Simple as that, no great problem, and in general we got on OK. We illustrated some books, which are awfully tacky but very useful. The Sex Maniacs Cookbook and some LP covers.

One of which was ‘Animal Games’ – how did you get into doing cover artwork?

At that time I had two children. You have to feed children. This involves buying food with money. Someone said ‘if you draw this picture, I will give you some money’.

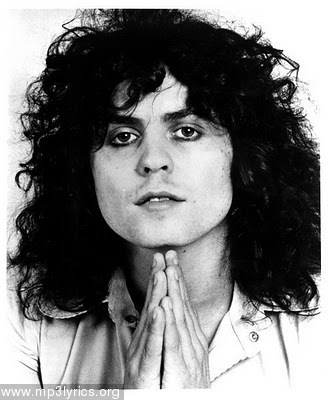

A very clear answer, I think. Looking back, what do you think about Marc Bolan in John’s Children?

Well, once you manage to fight through your own self-involvement, Marc clearly had something going, clearly. As for the merits of it – I wasn’t a great fan of Marc’s stuff, to begin with. I loved some of the songs he wrote while we were together in John’s Children: ‘Midsummer Night’s Scene’ had something, ‘Sara Crazy Child’ I always liked…

Well, once you manage to fight through your own self-involvement, Marc clearly had something going, clearly. As for the merits of it – I wasn’t a great fan of Marc’s stuff, to begin with. I loved some of the songs he wrote while we were together in John’s Children: ‘Midsummer Night’s Scene’ had something, ‘Sara Crazy Child’ I always liked…

And what would happen, would he bring something in on acoustic guitar…?

Yes, and we’d play it through the only way we could.

And how did he respond to it?

I can’t remember him ever saying ‘Oh no, that’s terrible’. It came out the way it came out. ‘Desdemona’, for example, very definitely was supposed to have a ‘Jailhouse Rock’ feel. We did it quite at odds to the way Marc wanted it to be, but I can’t remember ever him saying ‘no, I don’t want to do that’.

And he didn’t mind not singing?

He shared most of the singing, he did more than a lot of people think. He did ‘Jasper C Debussy’, the backing vocals on ‘Sara Crazy Child’… I would say he did about a third of the solo-singing.

He didn’t mind not being the lead singer?

No, he didn’t push for it. It was in the press releases at the times, he made it very clear that it was Andy who was the singer. But I don’t think Marc was ever ‘in’ John’s Children. He certainly wasn’t part of it, but what he did made John’s Children have any credibility at all, both at the time and afterwards.

What about the mod thing – if I understand it right, it was mostly he, if anyone, who was a mod… I remember seeing picture of Marc Feld, referred to as ‘King Face’ or something; didn’t he have some authentic ‘modness’?

Listen, I went to art school in east London. Most of the roots of the mod movement were from Mile End and Whitechapel, and then maybe over towards Shepherds Bush. And they were very, very smart city boys. Marc jumped on that, but Marc was nothing to do with it. But he knew what he was doing, again, and then he started drifting and of course, as you see at the end of JC, he’s starting to get a bit unkempt and you can see the Bopping Elf start to come out.

Listen, I went to art school in east London. Most of the roots of the mod movement were from Mile End and Whitechapel, and then maybe over towards Shepherds Bush. And they were very, very smart city boys. Marc jumped on that, but Marc was nothing to do with it. But he knew what he was doing, again, and then he started drifting and of course, as you see at the end of JC, he’s starting to get a bit unkempt and you can see the Bopping Elf start to come out.

I was in contact with the mods because in art schools, you had the fine art students doing a Diploma in Art & Design, then you had the other side where all the big companies in the city would have design departments so all their up and coming young lads would be sent to do some kind of design courses and that’s where they mixed, that where we met up.

We had a guy called Martin Sheller, who joined the Silence, who I knew at art college. Now he WAS a mod – his hair was right, his attitude was right, the way he spoke was right, his clothes were right. He used to come in – he didn’t ACTUALLY do it, but he almost walked in the morning and would do a spin ‘Hi guys….’ – pull the hat down over the eye a bit… now HE was a mod. And that’s what mods were about, and we weren’t that.

It sounds rather like the Radio Stars / punk relationship, in the way that we were not actually part of it but somehow got pulled in…

Yes, so while I don’t think Marc ever ‘in’ JC, it certainly suited him and I think he should get credit for that, because without him, we were just a bunch of yobs really. There had to be something more; not that I think we ever achieved it but at least with him there was a possibility.

Your playing with the Who thing was after JC, right?

No, it was during, but after Marc had gone, it was just me, John and Andy at that point.

Please tell Kiyohiro the Who Anecdote.

Well, if he wants to know the story, it’s quite straightforward. Simon had something to do with it. We were on Track Records, and we’d also ‘out-Who’d the Who’ at Ludwigshaven, as we all know. We’d been on tour with them, so we all kind of knew each other at that time, and occasionally used to go out for meals with Townsend on a social level, after that tour, and Entwistle.

Well, if he wants to know the story, it’s quite straightforward. Simon had something to do with it. We were on Track Records, and we’d also ‘out-Who’d the Who’ at Ludwigshaven, as we all know. We’d been on tour with them, so we all kind of knew each other at that time, and occasionally used to go out for meals with Townsend on a social level, after that tour, and Entwistle.

One day, I was up at Simon’s flat, I think, and Simon said to me ‘what’re you doing next week?’ And I thought, ‘I don’t know, mate, you’re my manager, you tell me!’ And he said ‘how do you fancy playing with the Who?’

I mean, how do you answer, that? Because, ever since I was at art school, I’d followed the Who avidly. Quite by chance, the first night they did the Marquee thing, the Maximum r’n’b thing, I was at college when loads of guys came round throwing out tickets. I went along after college, had few beers up in town, went along and I was absolutely blown away.

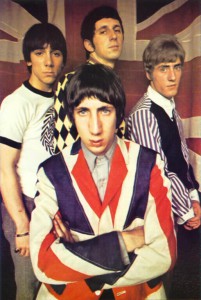

How good they were I’ll never know, because it just didn’t matter. The pure dynamic impact of what happened that night – I was speechless! People were jammed against the back wall because it was so loud, there was sweat and water running down the walls your back was soaking wet. I think Entwistle wore the Union Jack jacket the first time; Townsend had something else with medals and things which was causing outrage.

You could put the entire punk thing together and it wouldn’t have matches Townsend’s energy that night. The sound – Townsend using his 12 string Rickenbacker, the feedback was deafening, and he was just doing this flying thing with his arms, and the guitar was feeding back all round the Marquee, and this had NEVER happened before. I’d seen Beck, in Richmond, using feedback but he used it musically. Townsend didn’t do that.

And the song I loved the most was ‘Dancing in the Street’, because he used feedback – he’s a very rhythmic player, of course, – he was using the pick-up switch to make the syncopation, and in the solo – he didn’t play a solo, it was just guitar up against the amp… It was just trying new stuff, noises.

And then ‘Anyhow, Anyway, Anywhere’ came out, I went and bought that, and I invited Andy down to where I was staying, and we must have listened to it 50 times, absolutely pulling it apart – ‘listen to this bit, what’s he doing there…?’ So from then on, I was a complete devotee. I was only 18 or 29 at the time, and then, a year or so later, it was ‘Fancy playing with the Who for a week?’

But how was Simon in a position to ask you to do the gig?

Well, he’d done the deal already with Kit, he’d spotted the gap and suggested it, and Kit said ‘Oh, the guy from John’s Children, yes, why not?’ And they’d asked the Who, and they said ‘yeah, that’d be cool’ and that was it.

Well, he’d done the deal already with Kit, he’d spotted the gap and suggested it, and Kit said ‘Oh, the guy from John’s Children, yes, why not?’ And they’d asked the Who, and they said ‘yeah, that’d be cool’ and that was it.

And the records came round in a taxi…?

No, no, Townsend brought them round. Simon said ‘Oh, that’s good, because Townsend’ll be here in half an hour’. Townsend said ‘there you are, that’s the set!’. He said ‘go down to Pye Studios at Marble Arch in the morning. Keith’s kit’s in there, because we want to use our own back line. Tell the roadies exactly how you want it, have a bash around, get comfortable and I’ll pick you up from Pye at about 9.30’. So I went down to Pye at about 8.00 in the morning, got the kit all set up, they packed it all up and I drove up with Townsend in his Lincoln, this black American job. The first gig was at Southport.

No rehearsals?

No, nothing, I went straight on stage cold. But it didn’t matter because I knew all the songs. All the roadies were behind Entwistle’s stack giving me signals about endings. I only got into one bit of trouble and that was on the second gig, on a song called ‘So Bad About Us’. It had a syncopated rhythm was sounded very easy but I came in on the backbeat instead of the downbeat. But I caught up with it and it was came out OK. The rest went flying. We got to ‘Generation’ and I remember thinking ‘I’m just going to thrash through this’, because it would have been really naff if I started doing the Moon thing, but Daltrey made that decision for me by pulling the front half of the kit away. So I though ‘Fuck, what am I going to do now’? So I just dived on top of him and shouted ‘Fuck off!’

What was that supposed to convey on his part?

I’ve no idea, he just pulled the kit away, and so I just leapt on him. Then I just sat on the one of the bass drums – the kit was still together – two top toms I threw off, and I sat on the bass drum. I thought, well, let’s see if I can make something arty out of this, so I sat on the bass drum sideways, playing it with the pedal, and played the other bass drum with sticks.

On the last night, they blew me up with some bombs. I lifted about three feet in the air, all my trousers were burnt. It was during ‘Generation’ again.

Where were they?

In the Isle of Man.

No, not the trousers, the smoke bombs….

Under my feet. My white trousers were black, I thought ‘the bastards!’ I tried to jump at Townsend but he warned me off with his guitar. But it was a wonderful, wonderful week. (More here).

How did you join Jook? You knew Trevor White, right?

How did you join Jook? You knew Trevor White, right?

Trevor was going to replace Marc at the end of JC, although at that time it had broken down and it was nonsense, so ultimately that didn’t happen. It gets very complex here, too complex to get into. I didn’t know Ralf, didn’t know Ian. I’d joined a band called Cooper. It was a guitarist/songwriter and a bass player, so a three-piece, ostensibly a kind of Cream thing. We ended up on the college circuit. It was quite introverted but it was OK.

But then it became a bit lairy, John again was managing them. I don’t know what he was doing with his head at that time. I turned up at a studio with Giorgio Gomelsky, he was giving us what we thought were joints but it was actually opium, which really helped. And then one morning I turned up for rehearsals and there was some guy tripping round the drum kit, and he was my replacement. John had forgotten to tell me. You know this John Hewlett approach. I mean if John had come to me and said ‘Chris, this isn’t working out, they need this and that…’ I mean we’re all intelligent adults and you talk it through.

Anyway, Cooper then bit the dust. Cooper was signed to Apple, through John, and so I was in and out of Apple to get my salary, and I think at that point I met Ralph, just on a social level.

The plan was that Ralph and Trevor were going to Scotland to form a band, as they already had a publishing deal. I said ‘well, if there’s any space there, give me a call’. In the meantime, I was drawing those pictures we talked about.

They got a band going, with Ian and another drummer who was working out OK except he was a working drummer in Scotland, and he also had a music shop business, so he decided that he didn’t want to throw that up in the air just for a jog down to London. So they asked me, there was no skulduggery about it. We went and had a bash – funnily enough, it was just down the road at Barnet Rugby Club, and we drove past this house where we’re now sitting. And it all went well.

One of the elements of Jook that I remember well was that there was actually a very strong – sounds a bit hippy – camaraderie. And it was probably the straightest band that I’d been in, even with John managing them. There were times when we were a little bit concerned about how things were going, but among each other – me, Trevor, Hacker, and Ralph, who’s a lovely guy – there was a sense of trust. And that was quite a big bit of Jook.

What do you think of Jook now?

I loved playing in Jook; it was a fantastic band to be in. I really enjoyed it, probably too much in terms of actually taking decisions. We should have been more forthright in terms of what we would and wouldn’t do. It was such good fun and I enjoyed playing what we were playing so much that, each time someone said ‘Well we’re going to do some more rehearsing and then some gigs’, we’d say ‘great!’ whereas what we should have said was ‘we don’t want to do any more rehearsing, let’s do this sort of gig, that sort of gig, what are we actually doing?’ I probably didn’t put enough into that. So in one way it was great, in another a little bit sad that we didn’t push it a little more.

Do you have The Jook Anecdote please?

I remember Trevor, all punked up, with his denims, teenage tearaway hoodlum look. We were up at the Top Rank in Doncaster, supporting Wizzard. We were really rocking at this point, it was going really nicely, the lights were picking out different people. I’d do a thrash, and then Hacker would do something – rather Bad News, in fact – and then a light on Trev, a big screaming solo, down on his knees, slid across the stage, the light went across to Ralf, and then a glitch from the lighting guy and it went back on Trev, who was holding his guitar to one side with an irritated expression and was brushing his trouser down, where they got all dirty from his dramatic slide across the stage.

I remember Trevor, all punked up, with his denims, teenage tearaway hoodlum look. We were up at the Top Rank in Doncaster, supporting Wizzard. We were really rocking at this point, it was going really nicely, the lights were picking out different people. I’d do a thrash, and then Hacker would do something – rather Bad News, in fact – and then a light on Trev, a big screaming solo, down on his knees, slid across the stage, the light went across to Ralf, and then a glitch from the lighting guy and it went back on Trev, who was holding his guitar to one side with an irritated expression and was brushing his trouser down, where they got all dirty from his dramatic slide across the stage.

I looked across at Ian Hampton, was who barely ably to stand for laughter. Very Tee. It was almost a cartoon band but a lovely, lovely group of people to be with, I have to say.

We know how it ended, of course, so we don’t have to go into that (half of Jook joined Sparks, Chris and I got together in Jet). We know why Jim Toomey replaced you in Jet for a while (because you broke your leg). I remember you turned up at a BBC concert by Jet, where Jim was playing, and you heckled from the audience. “Rubbish! Get off!’ It’s very clear on the live tracks on the Jet CD (‘More Light Than Shade’).

‘I didn’t mean it! I apologise if it caused offence!

Not at all, it WAS rubbish, you were quite right… Jim Toomey’s spontaneous drum solo in the first verse of every song because he couldn’t remember what was coming next, Davey O’List playing the last bit of each song during the next bit…. What about this Irish punk band called Rudi, do you know them?

I’ve been told about them, but I’ve never heard them. What a shame that they chose that particular (Jook) song to name themselves after, ‘cos it was shit.

What did you think about punk, as you were a kind of onlooker at that time, in 76 and 77…?

To be honest, I don’t want to go down this ‘oh, it’s all been done before’ road, and I know the actual movement was bigger than that, but I didn’t really get into it. But my part in it was – well, the way we behaved in John’s Children on stage, and even to a small extent in the Who, I felt as thought I’d done that part of my CV. It feels as though there should be something more to it, as a movement, but maybe there isn’t.

What do you think of Martin Gordon’s mammals?

I’ve said all this before, it’s been great – the whole context of it, the playing on the stuff, the being in the places we recorded in (the Berlin radio studio used by Nazi Josef Goebbels for his broadcasts ), spending time in Berlin and being involved in it, it’s been fantastic. There is absolutely nothing negative about it, if only it were so with everything else I’ve done. And now with the live playing of it (with the Boston gig with Tristan Da Cunha) it’s reached new heights. The live Captain of the Pinafore is a masterpiece, a masterpiece!

The drummer, Steve Budney, spent three months trying to play as much like you as humanly possible, and I think he achieved it pretty well.

Oh, blimey, yeah! Absolutely. It must be quite difficult copying all that, I mean I didn’t have that pressure, I just did what I did and you did what you did with it. I’m not sure that that’s how he plays, really, that extrovert thing, I think he’s probably much more controlled. I noticed in the live version of Joy of Hogwash, there’s one particular break that he really gets into and he feels very natural; it feels like he’s stopped thinking about it and he’s just playing it.

Well, I think we’ve covered everything…

OK, let’s hear that Niacin CD you brought with you.

And so we did. We both knew that this would be our last meeting. He gave me his copy of the Keith Moon biography, in which he is mentioned in a footnote, and two model aircraft – a Hurricane and a Spitfire – for my son Chesta. 3 months later, Chris died.

Wow… never seen this interview before. I’m Sami, Chris’s eldest daughter… this is so Dad, great to see this online.. xx

Hey Sami – all well with you? Fond memories of Friern Barnet. And there is quite a bit of Chris hereabouts…